- Home

- Mark Kurzem

The Mascot Page 9

The Mascot Read online

Page 9

“I was too frightened to close my eyes and get in trouble again. I tried as much as I could not to see anything, pretending that the sun was blinding me and squinting my eyes. I couldn’t avoid glimpses of what was going on. Soldiers were prodding people into the building while others were hammering big planks of wood across the windows.

“Then I heard the outside doors being bolted. Soldiers put bunches of burning sticks and dead tree branches up against the building. In a flash it caught fire. For a minute or so it was deadly quiet, apart from the crackling of the fire as it took hold. The flames spread quickly and then terrible screams and wails began. And the louder the screams became, the more silent the soldiers were. Nobody laughed. They were hypnotized by the flames that rose higher and higher into the sky. Even the soldier I was with had forgotten about me. He, too, was frozen to the spot and entranced by the flames.”

My father paused again and took several steadying breaths. “Maybe they saw their own souls burning at that moment,” he said in a low voice.

“Then something snapped me out of it.” His voice was barely audible. For a moment he seemed to panic and gasped in air as if he were about to suffocate.

I gently encouraged my father. “Go on, Dad. Tell me what you saw.”

“Suddenly there was a movement from the building. It was a woman…my God!” My father let out a muted cry, as if he were seeing her at this moment.

“She was on fire. She dashed out from the huge wall of flame. Two children ran behind her. They were also on fire. They didn’t make a sound, as if I were watching a silent film.

“Then, before I knew what was happening, I heard cracking sounds and the woman and the children fell to the ground. They didn’t move. I knew they were dead. But the flames still rose from their bodies.

“I looked to where the noise had come from. I saw Sergeant Kulis and two other soldiers lowering their rifles.

“Kulis turned in the direction of the watching soldiers. Even though I was at the rear of the crowd, his eyes found me. He smiled and waved to me, shouting, ‘Partizani,’ as if to explain his actions.

“Without any thought, I turned and fled. I heard the sergeant call after me, but I ignored him. I didn’t dare look back. I ran through the streets until I reached the outskirts of the town, where I came across a small farmyard. I saw a shed there and crouched down behind it and covered both my ears with my hands. I didn’t want to hear the screams, which had reached a crescendo and could be heard even where I was now hiding.

“At that moment I hated Kulis and all of the soldiers. I wanted to be free of them. Then in the next moment I felt defeated. Where could I go? I slumped down, wishing death would take me, too. I wanted to be free from this misery.

“I looked up into a man’s face that was full of rage and hatred. It must have been the farmer who owned the shed. Before I could make a move to escape, he kicked me so hard that I went flying across the yard. But I didn’t feel any pain. I was numb inside and felt like I deserved his kick. For being with the soldiers, and for being in uniform.”

My father paused briefly and then went on. “I had no choice but to return to the soldiers,” he said. “I know I said that I would have preferred to be alone in the forest, but deep down this was not true. I was a frightened little boy.

“I made my way back along the road into town. The troops were where I’d last seen them—in front of the remains of the building. The screams had ceased. There was only the crackling and hissing of the wood as it smoldered and then collapsed.

“I can still hear the screams of those poor people as they clawed at the burning doors trying to get out.”

My father was again silent for several moments.

“Sergeant Kulis spotted me, and came over. He put his hand on my shoulder. I froze inside. I didn’t want him to touch me. I hated him. He’d done what other soldiers had done to my family. He was no different from them.

“Slowly the soldiers headed back to the station. Corporal Vezis, who always seemed so disciplined, went crazy, chasing some farmer’s chickens that had strayed onto the road and kicking at them like they were footballs.”

“Where did this happen?” I asked, half regretting that I’d urged my father to tell me the story.

“The soldiers never mentioned any names in front of me. We could’ve been anywhere. It was more than likely somewhere in Russia, given that later the soldiers told me that I was picked up in Russia, but I have no idea how far I had wandered in the forest before I was handed over to the soldiers. And how far did they take me in order to reach their makeshift barracks and then later their main camp? How far did we go on the train that day? No idea.”

“What time of the year was it?”

“Not long after I was picked up by the soldiers,” my father replied. “They told me later that they had found me in late May 1942, so it must have been early June the same year.”

“That would have made it summertime.”

“Exactly, and that is where I am confused, because my impression is that it was cold, and that there was snow on the ground.”

“They might’ve lied about when they picked you up,” I suggested.

“But why would they?” my father said, genuinely mystified.

“Perhaps to hide their involvement in this massacre,” I mused. “If only there was some way to find out more about the movement of Latvian troops.”

“Perhaps ‘Koidanov’ or ‘Panok’ is the key to where I was born. If that were the case, we could learn a lot about my movements and the soldiers as well.”

“What about this building?” I asked. “What was it?”

My father shrugged. “At that time I didn’t recognize the building as anything in particular. But I wonder now if it was a synagogue.”

“That’s what I was thinking,” I replied. From my limited knowledge of the Holocaust, I knew that it had been a commonplace occurrence. “The people were likely Jewish,” I added.

My father looked momentarily bewildered. “Sergeant Kulis used the word ‘partizani.’”

“The Nazis often used that term for the Jews they hunted in the forests. They also called them Bolsheviks.”

“I didn’t know,” my father said, visibly shocked. “To be honest, I wouldn’t have had the slightest idea who was Jewish and who wasn’t, even if they were my people. I was only five or six.” Then he added: “All I thought was that they looked like people from my village. Certainly now, looking back, I am sure that they were Jewish.”

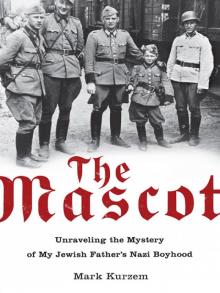

Another photo of my father, this time in his Wehrmacht uniform, 1943.

I was curious about the photographs and asked my father if he had any in his case.

“No, not a single one. The soldiers must’ve kept them as souvenirs for themselves. But nobody thought to give me one. I have another photograph,” my father said, eager to please. He reached across for his case. I heard the familiar clicks of its locks before he began to rummage inside it. After a few moments he held up a photograph. This one was a head-and-shoulders shot of my father in a military uniform I’d never seen before.

“Good God!” I heard myself say.

“You can’t tell because the photo’s in black and white,” he said, “but the uniform is blue—a pretty blue color like the sky. My first uniform. I loved it more than the other ones with their drab colors.”

“There were other uniforms? Other colors? How many uniforms did you have?”

“Three altogether. First of all the blue one, then we changed to a light brown one—”

“When was this?”

“I can’t give you dates,” my father answered, “but the first change must’ve been about six months after I got the blue one. Each time, a new miniature uniform was prepared for me.

“I remember being told that we were no longer ‘policemen’ and that we’d become members of the Latvian army and part of the Wehrmacht.”

“And that one was light brown, you said?”

My father nodded.

“

How long were you in that?”

“Until…” My father squinted, trying to recall. “It must have been in the summer of 1943, when Commander Lobe decided to take me north with his new brigade. That’s when I had to change to a green one, like khaki green, only lighter.”

“How long were you in the green uniform?”

“Until I left Latvia in 1944.”

“Just a moment,” I said, raising my hand. I repeated the details of uniform changes to myself, committing them to memory. It occurred to me then that much like a detective I was in dire need of a notebook to record the minutiae of my father’s story.

After a short silence my father spoke. I could sense his unease.

“There were other times”—he hesitated—“when I saw things…other atrocities committed by the soldiers. Sometimes when I was shunted to the rear of the troops I could only hear things. That was bad enough, but I guess they thought they were protecting me…as if I could be protected in any way from their brutality.”

My father fell silent. I could see that he had again become despondent. “I knew that the soldiers were doing wrong. If only I’d done more—”

I cut my father off. “What could you have done?”

“I should’ve tried to stop them.”

“What? You were a child.”

My father didn’t respond. I could tell that he was not convinced.

“Dad,” I said, “your life must have been hell with the soldiers.”

“I got used to it.”

I wondered silently how one got used to hell. Was it any easier for a child who had little memory or experience of anything better?

My father’s voice interrupted my train of thought. “They used me to get girls from the local villages when they wanted to have a party. They thought that because I was a small boy and so cute that the girls would be more willing to join them.

“One time we stopped for the night in a barn. The soldiers were already pretty drunk and unruly. They’d made this primitive distillery that they carried about with them on patrol in order to make samagonka.

“That evening they set up the contraption and had me watch over it until the bootleg was ready. Then it was my job to keep the soldiers’ tin cups topped up. Some of them forced me to swig the stuff so that before long I was as unsteady on my feet as the rest of them.

“A young girl, no more than fourteen or fifteen years old—she must have been the farmer’s daughter—came in with food for all of us. As she was passing it around, Corporal Vezis tried to kiss her. She laughed and pushed him away playfully, but I could tell she was frightened. She got out of there quickly. The other soldiers joked among themselves, saying that that was exactly what they needed—some girls.

“I kept on pouring the samagonka, but as much as possible stayed out of the way. At one point I felt Corporal Vezis’s eyes settle on me. He called me over and straightened my uniform. Then he got up and told me to follow him. I didn’t want to. I wanted to sleep. But he and another soldier pushed me out of the barn and down the path toward the village. On the way he made me pick some wildflowers—pretty ones.

“When we got to the village square, we hid behind a cart. Corporal Vezis and the other soldier quietly watched the comings and goings of people in their houses. Then a young woman appeared on the doorstep of one cottage. That’s when Vezis pushed me out into the open. In a whisper he ordered me to present the flowers to the young lady. I didn’t want to, but I didn’t dare disobey him, what with his violent temper.

“The girl was so surprised to see me, a boy in a uniform, swaying drunkenly at her door. I held out the flowers and she seemed touched. Then I nodded my head in the direction of Corporal Vezis.

“From a distance, the two soldiers must have looked harmless enough—just like any country boys courting girls—despite their uniforms. They waved at her in a friendly way, and she took me by the hand and went over. For a short while they talked and laughed among themselves, forgetting all about me. I was still drunk, silently willing myself to stay upright.

“Then the girl disappeared back across the square. Soon she returned with three other young women in tow. Together we all headed back to the barn.

“The party got into full swing very quickly. The women sipped on samagonka, and before long they were a little drunk as well. They began to dance for the soldiers. A few of the soldiers got up and were staggering around, trying to join in with the women, while other soldiers clapped and laughed at the way their comrades made fools of themselves.

“It had been more or less good-humored when suddenly the atmosphere turned nasty. Corporal Vezis tried to force one of the girls to sit on his knee and she resisted. Instead she gave a breathless laugh, pulled me onto her lap, and gave me a big cuddle. In a jealous rage, the corporal yanked me off the girl’s knee, almost ripping my arm off, and tossed me violently across the room.

“He then made a lunge for the girl, attempting to kiss her. She struggled with him, and when she broke free he made a grab at one of the other girls. All the while, the other soldiers looked on, clapping and cheering.

“You can imagine what happened after that,” my father said quietly, shaking his head in disgust. “I hid in a corner. I didn’t want to see what was going on, but I couldn’t block out the panting and the screaming, which seemed to come from all corners of the barn. My memories of what happened next are vague.”

My father seemed to be in pain and screwed up his eyes as if torn between his duty to visualize something more clearly and the desire to forget whatever it was he had witnessed.

“I must have fainted,” he said. “When I came round I could only hear the soldiers’ snoring. I peeped out and they were all asleep, scattered around the barn, wherever they’d collapsed in their drunken stupor.

“Then I saw that the girls were still in the far corner of the barn trying to clean themselves up. Their clothes were torn and they had been badly beaten.

“I wanted to help them. All I could think of was to offer them water. I tiptoed over to them. They backed away from me as if I were one of the soldiers, and then, without a word, they all slipped out of the barn.

“I stood there for a moment. I was bereft. They were repelled by me even though I felt I was on their side. I wondered if I should follow them and find refuge with them. I imagined I’d be able to tell them who I was: that I wasn’t one of these men, that I wasn’t anything like them. But then I thought: ‘Who would want me after I’d been with these devils?’

“Now, of course, I understand that the soldiers had been using me to lure the girls to the barn. I feel responsible for what had happened to them, even now.”

My father stared bleakly into space.

I shuddered.

I pictured my father moving amiably from one drunken soldier to the next, smiling as he solicitously poured the anesthetizing samagonka. I saw him on the doorstep of the young woman’s cottage holding the bunch of wildflowers.

I was overwhelmed by the vulnerability of this child immersed in a world of arbitrary and deliberate brutality. How had he managed to steer himself through it? He said himself that he tried not to stand out or attract any attention, never daring to disagree with the soldiers or recoil from their pornographic forays, which must have been unfathomable to a child of no more than six or seven.

I wanted to know more about these men, these soldier-puppeteers, who had controlled and exploited my father.

Yet it was not only the horror of my father’s experiences that had overtaken me; it was anxiety for my father and the possibly incredible dimensions of his story. Would people be able to accept the predicament of a child’s memory, lacking comprehensive details of names, dates, and locations? Could I? Thus far my father had revealed a handful of names and the letter “S” to add to the mystery of Panok and Koidanov. The remainder were impressions and sensations about incidents seen through the eyes of a child, shaded by bloody violence and an all-consuming fear of being discovered.

I looked

at the clock on the wall. It was nearly 4:00 a.m. The house was silent. Even my mother’s snoring had ceased. It felt as if the very walls of the house were listening to my father’s story in rapt silence. And now, like me, they waited to see if he would continue.

I rose and stretched my tired body, catching a glimpse of my face reflected in the darkened kitchen window. Opposite me, my father also stood to stretch. He smiled shyly at me, and his eyes betrayed no sign of fatigue. Instead their usual intense, vivid blue shone as if he’d just risen from a long sleep.

CHAPTER SIX

THE DZENIS FAMILY

My father and I sat down at the table again, as if recommencing a formal interview.

“How long were you with the soldiers on patrol?” I asked. “From when they picked me up, which they later told me was in May 1942, until toward the end of 1943,” he replied. “I wasn’t on duty all the time. Sergeant Kulis sometimes took me to visit Riga, the capital of Latvia.”

“How often?”

“At least twice, perhaps even three times; whenever he was given leave.”

“Does the length of time the soldiers claim you were with them make sense to you?”

“It does,” my father said, “because I spent one winter alone in the forest before the soldiers captured me, and then I was on patrol with them for a second freezing winter before I was taken to Riga for a short time in the late spring of 1943.”

“Do you remember much of 1943?”

“I do,” my father answered, “especially after reaching Riga, where life was more stable. When I was with the soldiers on patrol, nobody paid any attention to dates and times as far as I could tell. It was chaos. And I was older in Riga. I remembered when people mentioned dates, and I was learning to read, so I could follow details in newspapers and magazines.”

“If these dates are correct, the extermination of your village, wherever it was, must have taken place in 1941.”

“Late in 1941,” my father said.

“Why late ’forty-one?” I asked.

The Mascot

The Mascot